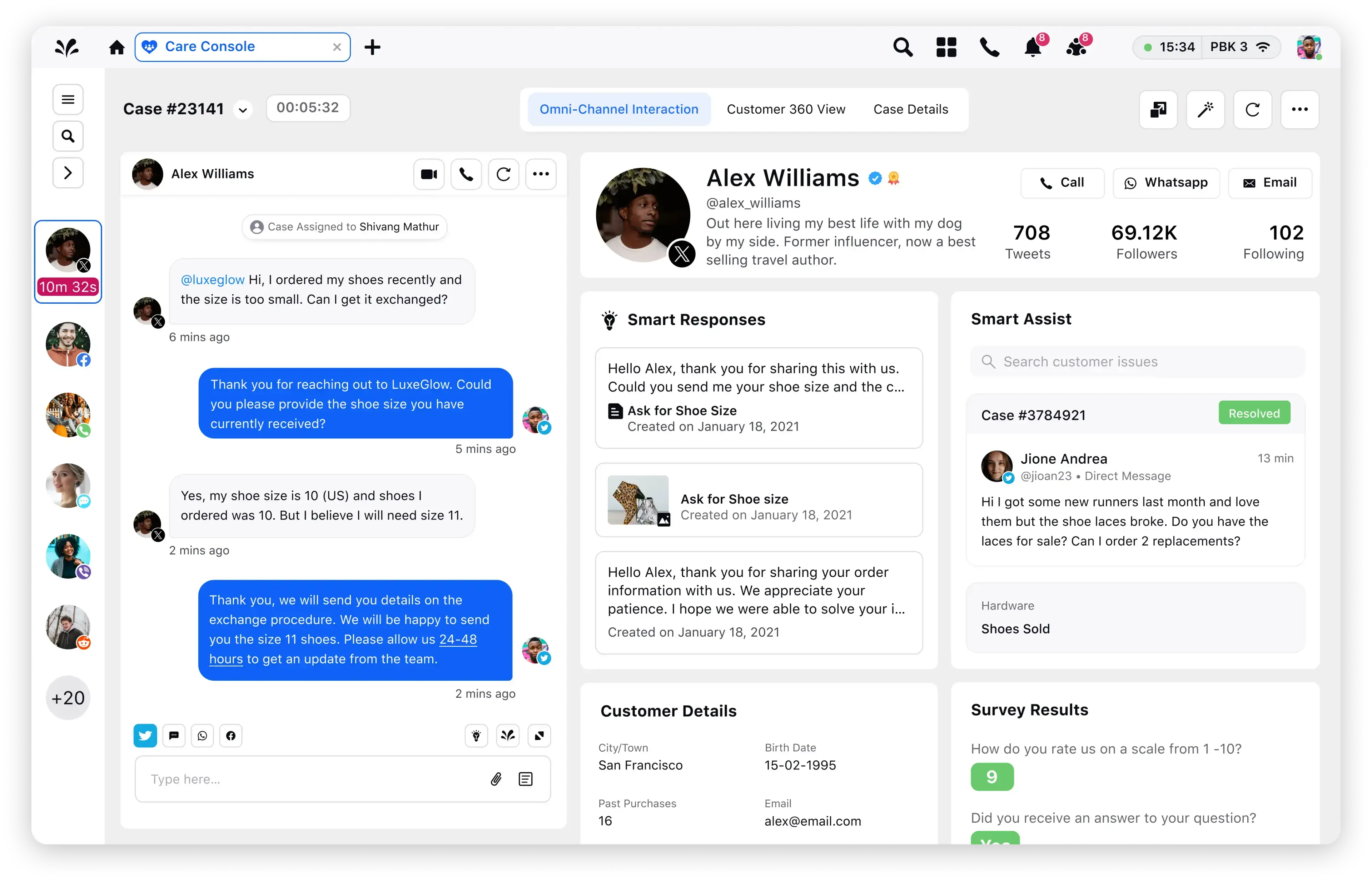

The AI-first unified platform for front-office teams

Consolidate listening and insights, social media management, campaign lifecycle management and customer service in one unified platform.

Episode #112: The Proven Power of Category Design, with Peter Goldie

Brands, products, or companies that define a new category — and become the design standard for that category —derive most of the profit from that category. It’s a simple idea, but a challenge to execute. Peter Goldie, category designer and advisor, joins me today to talk about his real-life experience helping companies create categories that drive business value.

We also talk about his time at Macromedia, the meteoric rise and fall of Flash, and Al Gore’s chicken hypnotizing stories.

Peter Goldie is focused on the emerging discipline of Category Design — helping companies define the category they are in and align their product and company so that they can become the Category King — taking the lion’s share of profits. You can find Peter on LinkedIn, or at www.categorydesign.co.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

Grad

All right. We’re back. It’s another episode of The CXM Experience. And as always, I am your host, Grad Conn, CXO, chief experience officer at Sprinklr.

And today… I always love our interview shows, but I am particularly chuffed today. I have on today’s show, Peter Goldie. Peter will introduce himself and talk a little bit about his background, because I won’t be able to do it justice, but he’s a category designer. And when I first started at Sprinklr three years ago, one of the very first things I asked everyone on my team to do is to read a book called Play Bigger. And if you’ve not read Play Bigger, stop this podcast right now. Download it on your Kindle and read it. And then come on back. And we’ll continue from there. I’ll just wait a second here.

You done? Okay, good. Play Bigger. is a really influential book. It’s been out for a few years now. But it’s gathering momentum on its influence. And the basic concept of Play Bigger is that brands, products, or companies that define a new category, and become the design standard for a new category, derive most of the profit from that category. And there’s a whole bunch of things like Geroski curves, and other very interesting concepts, which we’ll dig into with Peter. But for now, this is all about how do you dominate in a category in tech. And I think the biggest influence that Play Bigger has had from my perspective is it has really changed the way the VCs invest. The principle of Play Bigger is that it, say in the dotcom years, someone would invent a category. Say, eBay. You come up with online auctions. And the VCs would rush to invest in a lot of me-toos. You would see a lot of secondary companies thinking that they might get gobbled up or grab some secondary market share. The principles of Play Bigger are such that VCs now recognize that once there is the dominant design leader in a category, there’s very little additional profit to be made. So people are doubling down on the leaders. It’s changing the investment landscape dramatically in Silicon Valley. But the other thing that’s really cool about Peter is that Peter and I went to school together. So Peter is someone I’ve known most of my life. Since I was 17, I guess. And Peter is a fellow Canadian, lives in the US in California now, like myself, just on opposite coasts. And it’s really a fantastic honor to have him on the show today. Welcome, Peter.

Peter Goldie

Hey, thanks, Grad, I am super excited to be here.

Grad

Well, it’s really quite amazing actually that we’re having this conversation. It’s funny how life is and how funny how circles interweave. But let me let you start for a second, just do a capsule history of the Peter Goldie story here. What was your journey from, Converse 85 leather jacket wearing to sitting in your home in California today. And then give people a sense of your background and experiences and the journey you’ve been on?

Peter Goldie

Okay, well, for, I don’t know, 25 or so years focused on growing software companies in tech and focused on a variety of skill areas. I was doing product management, product marketing, marketing, and then a bunch of exec roles as DPs and GMs, and CMOs and that kind of thing. And I was super lucky to have been involved in building a couple massive categories that didn’t exist. We can talk about some of those to whatever degree. And then five years ago, I switched from player to coach, and I work on helping leadership teams do this category design process. And it was all precipitated by the publishing of the book Play Bigger. And having worked on one of the stories in the book at Macromedia, with the authors of the book, Al and Chris and Dave, we all worked on this experience campaign to build out Macromedia’s presence as evolving from… at least the Flash business… evolving from an animation tool to a user experience design tool.

Grad

Well, it is an amazing journey you’ve been on it’s so cool. It’s funny how life is so unpredictable. I remember when you went into tech. I mean, you were early. Very inspirational to me actually. It took me a little while longer to get my courage up to leave. But you were very inspiring to me to get after the thing that you had passion for. So I was. I’ll just leave you with that for a second. But let’s talk about the Macromedia story because it is in Play Bigger. And I think the essence of category design is to… correct me if you disagree with me here, okay. But I think the essence of category design is to almost elevate your company’s product or the thing that you’re making, from the thing it may be doing today, to the thing that it may be able to do tomorrow. And it’s almost like it expands or widens the field of its possibilities. And that’s what it feels like happened at Macromedia. But you know, I wasn’t there. I wasn’t on the inside. Tell me what a little bit that was like and what you were trying to do. And maybe what inspired you to try to create a new category. What was the impetus to do that in the first place?

Peter Goldie

So when we were working at Macromedia, we had a whole bunch of web tools, Dreamweaver and ColdFusion, and Flash. And what we saw was people were not having great websites. The user experience was just not good. They weren’t using the tools in the best way possible. And we saw an opportunity to have both products and standards that would allow for a better user experience, and for companies to basically make more money with their websites. And that was really the impetus for a whole series of activities around experience. And we had a campaign that everything rolled up into called Experience Matters.

Grad

Oh, yeah, I remember that.

Peter Goldie

And we focused on getting our products aligned with that.

Grad

So, basically, you saw a problem, right? You identified a problem. Was there a technology change or leap, or something happening that allowed you to more easily address that problem, then you could have a few years before?

Peter Goldie

Well, we happened to have a technology that was unique in the Flash platform. And what happened with Flash is we had a very efficient way of transmitting data from the server to the client. So from the backend servers to the web page. And at the time, when it was just basic HTML, there were a lot of issues, because imagine back then we don’t have fiber and super high speed broadband. People are still using modems, the internet is slower. And webpages will take a long time to load. And we had a technology that made that work a lot more smoothly and a lot more quickly. And the opportunity was to have webpages, react and load better. And also to start to provide multimedia as opposed to those old gray pages with the blue and purple links and large text.

Or, another great example, was even just on the pure cost saving side. E*trade was one of Macromedia’s clients. And if you can imagine someone’s looking at their stock portfolio. With Flash, you could put a little widget on the page. and it was like a direct connection to just the stock data. We don’t need to reload that whole page of all kinds of information, we just want that stock price updated. And it could be updating like live in real time with so little data being used. And a great customer experience, because they’re seeing the stock picker tick away live instead of sitting there reloading a whole page of information.

Grad

Interesting.

Peter Goldie

So, there was a technology fit to improve the user experience. And then we just went all in on, well, what else would it take to help companies make more money on the web by improving the user experience? It was about training. It was about deciding on some standards for how UI would work. What would UI look like, what should a video button look like? And then building those things into the products. And then making people aware of the opportunity that you get a business benefit by delivering a better user experience. So we had Forrester and IDC and these analyst firms come in and do analysis and do research and look at what happened to companies that delivered a better user experience. And yeah, their websites were more successful, and they did more business. The technology we had we called Rich Internet Applications, RIAs.

Grad

You invented that?

Peter Goldie

Yeah. In fact, I think that term was coined by one of the Allaire brothers, who were with Macromedia at the time. And then we did a whole campaign around Rich Internet Applications and what they are, and the value they provide. And then that layered into the idea of experience design, and the idea that instead of just UX designers, you could have experience designers who are looking at a bigger picture. And we coined the phrase Experience Design.

Grad

Talk to me a little bit about the analysts? Now, one thing that’s kind of interesting, I’ve heard this a couple of times now… and I’m a massive fan of the analysts. And I’ve worked very closely with them for a number of years. So this is not meant to be disparaging in any way. But I have heard that typically, in category design, analysts are generally a trailing indicator, not a leading indicator, right? Like no analysts had the whatever category Uber is in, ride hailing services, no analysts had ride hailing services as a category prior to Uber coming along. Right? Makes sense. So, how did you how did that work in your case? And did you, or were you able to, or how did you influence the analysts to then start to recognize experienced design as a category?

Peter Goldie

Well, I think at this time, I mean, we knew there was something big that we could make. But the word “category design” didn’t exist, at that time. We were just thinking business opportunity. So I think what happens today, it’s far more challenging. Back then we said, there’s this new thing called RIA. And IDC said, great, we’ll write a paper on RIA. That sounds interesting. But today, if you’re inventing a new category, now that this is a thing, and people try and do it, one of the most difficult things about category design, I would say, is getting alignment with the analysts. Because they have now their own interest in creating their category. So if you go to Gartner, they want to name the category. And they want their analysts to be the thought leader in the field. They don’t want one single vendor to be the thought leader in the category. It’s definitely a challenge. And we faced this with many clients where we create a category name, they go present it to Gartner. And Gartner says, No, no, that’s not a category. No, our category is the category. And that’s where it just takes persistence, and aggressive marketing, to go build that category in the minds of people. And then if it gets built in the minds of people, the analysts will follow in line at some point. But it could take years and years.

Grad

Well, let me step back a tiny bit for the folks that are listening in. Because some people may be like… that Macromedia story is amazing, by the way. But they may be like a little lost if they’ve not yet read the Play Bigger book, even though at the very beginning of this, I said very clearly stop the podcast, read the book and come back. Maybe people didn’t do that, right? I think one of my favorite stories in the book was a story of Clarence Birdseye. When I first read the story — I’m obviously familiar with Birdseye frozen foods. Who isn’t. right? It never occurred to me in a million years, that Birdseye frozen foods were named after someone named Clarence Birdseye. I just thought bird’s eye was something that they made up or something. And there’s actually a real person named Clarence Birdseye, turn of the century, like back in the early 1900s. And the way that they described what he did, and then I want to get you to jam on this with me a little bit, is that he basically had three ingredients. There was an innovation, there was something new that was changing the landscape of the country. And then there was a gap. Right? So innovation, new, gap.

And the innovation was, he was working for the US government, with a number of people in the north, and he was noticing that when they were fishing, they would pull fish out of the water, throw them on the ice, throw a block of ice on top and flash freeze the fish. And so the whole concept of flash freezing, was something that Clarence brought back with him when he came back to New York. And he started experimenting with flash freezing using liquid nitrogen. But that was essentially invention. The second thing… or innovation, depends how you look at it. The second thing is that at the time, electricity was spreading like wildfire through the world, especially the United States. And so for the first time people were starting to have refrigeration and freezing available to them. Obviously, very early days, and it took decades for Clarence to get the full supply chain in exactly the spot you’d want to get into. Because when he started, there weren’t refrigerated trucks. There weren’t refrigerated sections to the grocery stores. People were just getting refrigerators and freezers, so there’s a lot of work to be done. But he saw the opportunity. Like Amazon, seeing that the internet is going to be big one day kind of thing.

And the third thing is he saw a gap. And the gap is the interesting thing to me. Where at the time, there was fresh food, which was delicious, but has limitations in terms how long it lasts. And then there was canned food, which tastes almost nothing like the actual fresh food, but lasted for a long time. And somewhere between lasting for a long time, but kind of tasting yucky, and tasting delicious, but not lasting very long, he saw a gap for frozen food, which was food that tastes very close to fresh, but could last for a long time using this flash freezing innovation. And I thought that was a really crisp way of essentially summarizing how he got to a whole brand-new category called frozen foods. Which is… I don’t know what the percentage is, but it’s a pretty significant component of how many people eat food today. I’d love your feedback or reaction to the Clarence Birdseye story as well, and how you’ve interpreted that. And then any examples, or just jam on this for me for a second. Because I think it’s an easy way to point to what is category design and what’s not category design? It does feel sometimes like people are trying to create a category where it’s like, come on, that’s not really a category. You’re just naming it that thing. Let’s just go on that for a few minutes and see what your reaction to that is

Peter Goldie

Yeah, well on the Clarence Birdseye story, you covered it very well. One thing that I find most interesting about that story is that part of category design is looking at the whole problem, and what it takes to solve the whole problem. And typically, one of the best parts of the process is, when you step back and take a look at that, you discover you’re not solving the whole problem. And typically, a company going through the category design process formally will end up with an altered product plan in one way or another. That’s one of the side benefits and parts of the process. And I think in the Birdseye example, it’s when you look at that whole problem, there’s what you can solve. But then there’s the bigger ecosystem of what has to happen around you to support you solving that problem. And that’s the thing that’s so interesting about Birdseye is that he had to rally a complete ecosystem. He had to get the grocery stores to install the freezers. And he had to get the trains to install freezer cars. And it took forever, and he went bankrupt. I mean, his whole story, when you go deep on it, it’s a very interesting story of all the failures that he went through. But the idea of rallying a whole ecosystem around you to deliver on the needs of customers, is I think one of the important takeaways of that.

Grad

That’s really interesting. I didn’t know he went bankrupt. But he sounds like a total badass. I mean, just to take that on. That is super impressive. I love people that do that kind of thing. It must have seemed almost impossible from the perspective of 1910. And he was like, yeah, we can pull this off.

Peter Goldie

Yeah, yeah. His story is totally incredible. And then, your further point on category design, you know, is it a real category or not a real category? I think that’s where the magic of category design comes in. I mean, if it’s well done, it’s a real category. And a real category can be created with words. It’s not necessarily about product, or brand. If it hangs together, and tells a compelling story, and it makes sense to customers and investors, then it’s a category. And there’s no reason categories can’t be subcategories, or adjacent categories to existing categories. When you think of some of the original examples, also from the book… Salesforce, when they were invented, CRM was a category, right? But cloud CRM, well, that’s kind of a different category. That’s a spin on CRM. And cloud CRM is a huge category.

Grad

Right, right.

Peter Goldie

You know, we’ve created a lot of categories where it’s really just using words to differentiate the value you’re providing. For one example, there was a company that was in the workforce management space, and had a time and attendance set of products. So that’s punch clocks and timesheets and things like that. And that’s what Gartner would call them, time and attendance vendor. And we said, well, we want to deliver more value to clients than just punch clock time. And we’re going to create a new category. And we’re going to deliver time intelligence.

Grad

Oh, interesting.

Peter Goldie

So, the category is time intelligence. And when you define time intelligence as, that’s when a company treats its time as valuable as its money. When you think of your finance departments, and everyone counting the money, then you might want to have time intelligence. And that’s a new category of products. So our products that we deliver are going to give you time intelligence, and that’s going to help you figure out are you spending your time wisely? If you have 2,000 employees, you have a million hours at your disposal each year. And are you spending those hours wisely?

Grad

Looking at time as an asset.

Peter Goldie

Totally. And so this company, Replicon, they say they’re in the time intelligence category now. And yeah, it’s just words, it’s made up. But it’s meaningful, because it’s defining the value they provide. It’s a different way of thinking, it’s a different kind of product for customers to buy. It’s in its new category. And another interesting thing about that, is it again, led to that idea of Well, what does that mean, for your products and services if you say you’re in this bigger, more important category now?

Grad

So what happens when everybody’s trying to create a category? Eventually you get to some sort of burnout rate on this, right? I saw the other day, a car company had a new car, they said it’s a CUV. And my immediate reaction was, No, it’s not. That’s not a thing. You just made that up. It’s not a real thing. It’s a small SUV, though, that it is. It’s not a CUV. What happens when there’s a burnout on category design? What comes after category design? I’m sure you must think about this all the time. Sometimes what happens is the pendulum swings one way, and there’s value in swinging it back again, and catching it on that early part of the arc. Any thoughts on that, or I’m sure you’ve had some beer debates on that with your fellow category designers.

Peter Goldie

The purpose, I mean, down at the core of category design, we haven’t really talked about this much yet, is to not be slugging it out with competitors. Because who wants to enter a market space and have 100 competitors and be scrapping for 3% market share? The idea behind category design is if you can show that you solve the problem successfully, and that it’s a nuanced or different problem, and a different solution than other people are providing, then you have a unique category. And there’s the opportunity to have a new category. I mean, there’s any number of ways you can split up the pie of people buying products and services. And if you have your own category that’s different than what other people are doing, and they want that problem solved, then they have nowhere to go but you. Now, there might be some substitutes that are in very similar adjacent categories. But if they really need to solve the problem, and you’re solving it for them, then you are the solution. So, I don’t see categories going away, or people not being able to introduce new ones. Except if you do it poorly.

Grad

There’s always this accepted wisdom, right? You can’t do this, or you can’t do that. And then someone does it. It’s like, you can’t break the rules unless you break them brilliantly. It’s a classic trope in entertainment and music and stuff like that. One of my favorite examples is on Broadway. If I were to go to a producer, let’s say… how many years ago would this have been… maybe six or seven years ago. If I went to a producer six or seven years ago, so mid-2010, 2012, 2015, somewhere in that zone. And I said I got a great idea for musical. Okay, what is it? I want to do a musical about 9/11. They would be like, dude, get out of my office right now. Like right now. Okay, I got people coming in here to get you out of here unless you get out of here, like skedaddle. And then they did Come From Away, which actually is Canadian born in many ways. And it’s brilliant. It’s an amazingly brilliant way of doing essentially a musical about 9/11. They brilliantly glance off the side of it and tell essentially, a different story, which is about the amazing people in Gander, Newfoundland. This is very much a human story of caring, and love against the backdrop of 9/11, but far enough away that you can actually deal with it, right? It’s still very emotionally impactful for a lot of people, but you can start to get there.

And I think that’s true in a lot of fields. In medicine, people are constantly being told that’s never going to work, or that procedures crazy, or that’s insane. And then that becomes the standard, right? So, let’s talk a little bit about category design. You’re a category designer now. You’ve been doing this for a long time. You’ve actually done it in real space, not just as a consultant, but you actually did it in real life. And then you’ve gotten to play with the Play Bigger team for a long time. So, if I’m a business, there’s a bunch of questions that I might have. Let’s assume I’m a tech startup of some kind. The first question I’m thinking… and I’ve invented some technology, and I’m thrashing away, and I’m starting to try to get some customers. At what point should I think about engaging in a category design process? What size company am I? Where’s my product? That’s the first question. And then what I’d like you to do is take me through, once that stage is encountered, then what does it feel like? What does that process feel like? And how long does that take to get to a point where I feel really comfortable about talking about time intelligence, for example?

Peter Goldie

Well, from a stage standpoint, absolutely right away.

Grad

As early as possible?

Peter Goldie

As early as possible. There’s a concept in Play Bigger called the magic triangle, which is product, company, and category as three points of the triangle all needing to work together at the same time. So the traditional thing that happens is you start a tech company, and it’s all about product. Product market fit, I’m going to do lean startup, we’re going to search for all of that product thing. And then you think about, okay, what kind of company do we want to have? Where are we going to be, what’s our culture? All that. And then categories could be something that you never think about ever. Or you think about way down the road.

But the opportunity to think about category, right out of the gate, is to get the company right, and the product, right to fulfill that category vision that you can create. So, I would encourage anyone to start immediately on category design. But that doesn’t mean hiring people. Read the book. The book is a DIY guide. You don’t need to hire people, just do that thinking. Because it’s super helpful to set you up to be in the right place. But the process, if you engage someone to help you with it, is to basically work through six or seven steps of the process of creating the category. And there are deliverables along the way for each of those. And nowadays, it would be Zoom workshops. I just finished up a project that was seven Zoom workshops over a four-week period. And lots of work in between.

And, the stages of category design are digging into the problem. We spend a workshop talking with the founders and the key folks about what’s the problem we’re trying to solve. Go super deep on the problem. And then start to explore what’s the right solution to fit that problem. And if you really get the problem really well defined, the category name emerges. You figure out what that category is. I mean, it may take brainstorming hundreds and hundreds of names, but you get to a name for the category. And then probably the most important, I think the cornerstone of the process, is something called the point of view, which is the story of the problem we’re solving and why we’re the right people to solve it. And the great outcomes that people get when that problem is solved. So it has a story structure to it. It’s an emotional story. It’s probably 800 words long, give or take a couple 100 either direction. And it gives you the company values, vision mission, all wrapped up into one very compelling story of what you’re up to in creating this new category.

Grad

Cool. What was your lightning strike at Macromedia?

Peter Goldie

It was the Macromedia Experience Forum. And it was our opportunity to go higher up in organizations. We were selling to developers and designers. But we wanted to talk to the CMO and the CEO about the business value of having a better web experience. So it was this whole experience matters piece rolled into a forum. We hosted a day event. And we got our sales teams going and inviting out the CEOs of their customers, and the CMOs, and the heads of design. And we had a big event, and it was a one-day event. I hired Al Gore as our keynote speaker.

Grad

Nice, nice.

Peter Goldie

And at the time, he wasn’t known for climate. This was one of the first public presentations where he talked a bit about climate.

Grad

What year was this?

Peter Goldie

This would be 2005.

Grad

So he was just recently… Al Gore was pretty hot then. Okay. All right. That’s very cool.

Peter Goldie

Yeah. But what was interesting about Al as a keynote speaker…

Grad

Oh, Al? Hello. Okay.

Peter Goldie

Yeah, my buddy Al. What was interesting about Vice President Gore…

Grad

There we go…

Peter Goldie

Was he had invested in a media company called Current. And it was a hip, new media company. And they used Flash as their platform and had a great experience. So that’s what he was there to talk about, in theory. Although he is not someone you can control as a speaker. And he definitely spent a lot of time talking about how to hypnotize chickens on the ranch. It was amazing. He was great. But we also we also had a lineup of other great speakers. We had Tim O’Reilly…

Grad

Yeah, nice. I know Time well.

Peter Goldie

And Tim’s a great speaker. And extra interesting about Tim was, he was in Europe at the time. And we webcasted him in using our technology, which was called Breeze, which was a Flash-based video conferencing service. And that was all new at that time. Like, video conferencing wasn’t a big deal. So he presented from Europe. And that was really cool. And then actually, this Forrester analyst, Harley Manning, gave a presentation as well. So we had this great day. We had CEOs in, and we launched this whole experience design thing. And it worked out great.

Grad

That’s an awesome story. I love the chicken hypnotizing. I’ve got to look into that. I want to come back to category design for a second. And then I want to wrap up with some of your thoughts on the end of Flash, because I heard there were some interesting parties and stuff like that. We’ll come back to that in a second. But this idea of starting with the problem, you’ve mentioned this a number of times. Do you find that most companies are not clear on the problem that they’re solving? Or they’re not clear on the bigger problem that they could solve?

Peter Goldie

Yeah, surprisingly, they’re not clear on both of those. You stray away from it. When you get started it’s like, what’s the problem we’re solving? But then it’s all focused on what do we have? What do we have? And how does it work? And how can we make it better? And there’s not often a look at stepping back at what is the bigger problem? And it’s just clarity around the problem. In marketing, it’s that classic, what’s not the benefit, let’s go for the next benefit, the end benefit, and the end end benefit. It’s doing that kind of exercise around the problem. And just going that layer deeper, and it usually leads to some great insights. Or at least clarification of we’re solving a bigger problem or a more important problem for people,

Grad

If I’m on the $25 plan, right? I’m not, this is theoretical. If I’m on the $25, the $24.99 plan, I’ve purchased the book, and I I’m suspecting that maybe I haven’t fully identified my problem. Are there any tricks or exercises or thought exercises that I can go through to alter my mindset? Because what I find often, is that everybody that I work with in this sector… super smart. Again, we’re all working with super smart people all the time. So the barrier is not an intelligence barrier. The barrier is a mindset barrier, right? We get locked into ways of thinking that we’re not even aware of some of the invisible chains that we’ve bound ourselves with. So, if you’re trying to break that mindset, and you’re trying to get outside your features, today’s product, today’s customers who are screaming at you, all that kind of stuff. You’re trying to get to that higher order problem. How would you coach someone to do that on their own?

Peter Goldie

Well, the technique that we use that works very well, is it’s about having multiple people involved. So it’s not just your brain. What we do is we have everyone on a team write out, what is the problem that you’re solving. Okay. But then, when they do that on their own, and you throw up seven people’s answers, they’re invariably different. And then you get into a robust discussion of the differences and the commonalities. And that’s the discussion that leads to a redefinition of the problem. But it’s about the communication side, and everyone sharing their differences of their ideas and the way they view a problem. That’s the discussion that leads to a better problem definition.

Grad

That’s very cool. I interview a lot of CMOs on the CXM Experience. And one of my favorite things is to ask them, what’s their definition of marketing? I’ve never had a single CMO say the same thing.

Alright, we’re on time, and you’ve been incredibly generous with your time. So, I want to thank you for that. But before we wrap, Flash has been discontinued. What are your feelings around that, emotions around that? How did you deal with that? Is there a bottle of Jim Beam just out of the camera right now? How do you react to something like that when you put so much of your life into something? As happens so often in technology, one day, it just simply disappears.

Peter Goldie

Yeah, it really was a meteoric fall that Flash had. When I was working on the business, we got to a billion users. And it was the largest software footprint on the planet, there was no software the people had as substantially as Flash. And ultimately, and it’s covered in the book, Al talks about it a bit in the book, the downfall of Flash and some of the mistakes that were made that caused that. But yeah, for me, it’s definitely emotional. I mean, my license plate on my car is FLASH MX.

Grad

Are you serious? That’s awesome dude.

Peter Goldie

That was a big launch for me. It’s definitely bittersweet. I mean, the technology was not in shape to deal with security in the way things need to now so. So that was sad. But it’s just a clear sign to move on. Maybe I need a new license plate now.

Grad

If it makes you feel any better, there’s a number of really great license plates in Seattle, often on really nice cars. And there’s a Ferrari that drives around Seattle and the license plate is HD DVD. Ouch. My favorite though, on another Ferrari. There’s another license plate, this is this is a good story. And the license plate simply says THX which actually stands for thanks, it’s THX BILL. Thanks, Bill. Isn’t that great? That’s a hot license plate.

Peter Goldie

I bet there’s some good DeLorean license plates.

Grad

There are some good DeLorean, like a Doc Brown, for example, could be a good example of a good DeLorean license plate. Yeah, that’s a great story. We’ll tell that another time. Well, Peter, it’s been a real honor having you on today. It’s great seeing you again and great catching up. And I look forward to seeing you many times more in the near future. I’m going to thank Peter for being on the show today, and for the CXM Experience, I’m Grad Conn, CXO at Sprinklr. And I’ll see you… next time.